When I went to meet Muhammad Ali the morning after I graduated from high school, my enthusiasm was tempered by my growing recognition of what was happening to him. I’d seen Ali light the Olympic Torch the previous summer, I knew all those fights had taken a toll, but it didn’t totally sink in until I shook his hand and felt it shake. I verbalized my admiration for him; it was a one-sided conversation.

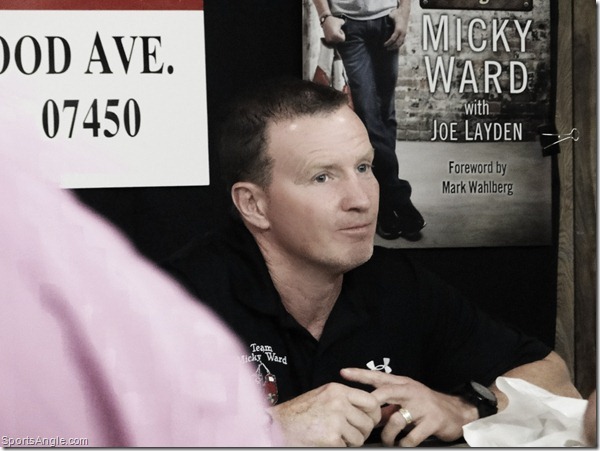

Compared to Ali, I was relieved to find Micky Ward seemingly in relatively good shape when I went to the North Jersey book signing for his new memoir, “A Warrior’s Heart,†last Tuesday. I came away thinking that Ward looked and sounded pretty good, considering his former line of work. And honestly, that’s what we want when we seek out the heroes of our youth.

We want to be able to say, “He looks good.â€Â

*****

There’s a certain type of guilt inherent with being a fan. We’ve loved our heroes for being larger than life, impervious to pain, brave beyond anything we could imagine for ourselves. Even if deep down we knew they’re flesh and blood and basically as flawed as anyone else, that was never what we needed them to be.

As I explored recently for The Classical, I loved Arturo Gatti for the very traits that would eventually kill him. Having watched him since high school and attended several of his fights, I kind of felt like I knew him, though I’d only met him once in passing.

As such, I never missed a single one of Gatti’s fights, but there was always a palpable relief when they were over. I hardly desired to consider that the impact of all those punches would be felt long after the final bell had rung. I felt the blows vicariously; he felt them physically and emotionally, which was obviously far more taxing and lasting.

This isn’t limited to boxing, of course. Lord knows what MMA fighters are doing to themselves and each other, and virtually all the professional wrestlers we grew up watching portray living cartoon characters have become varying degrees of Randy the Ram.

Football is probably the most alarming case, in that you can’t write it off as a niche sport. I still have two Junior Seau jerseys dating back to his days on the Dolphins, a testament to how excited I was when they traded for him; he was a terrific player with a colorful name and haircut, and he was a beast in Tecmo Super Bowl.

Though I never took the time to think about what years and years of helmet-to-helmet collisions were doing to Seau and his brethren, nobody else did either. We just kind of figured they’d stop playing at some point, their wounds would heal and they would pass their days posing as figureheads for restaurants and playing in golf tournaments.

Seau’s death gave people pause, but like any other Twitter-borne news cycle, it faded away rapidly after everyone finished waxing poetic. Despite what you may hear, football isn’t going anywhere, not so long as people have fantasy teams and bars sell 25-cent Buffalo wings on Sundays. Our guilt is mostly of the silent variety, manifesting late at night during reruns of Real Sports when they do segments about concussions or demonstrate how Earl Campbell can’t walk anymore.

After the Gatti essay, I’ve had a few people ask me if what we’ve learned about concussions and things of that nature affect my enjoyment of boxing, football and such. Unequivocally, the answer is yes. But to stop watching would affect no real change; we’d all have to stop, and that’s never going to happen. Instead, we rationalize.

After the Gatti essay, I’ve had a few people ask me if what we’ve learned about concussions and things of that nature affect my enjoyment of boxing, football and such. Unequivocally, the answer is yes. But to stop watching would affect no real change; we’d all have to stop, and that’s never going to happen. Instead, we rationalize.

Paul Williams was in the news recently for all the wrong reasons, and it caused me to reflect on the one time I saw him in person, when personal favorite Sergio Martinez knocked him literally unconscious a year and a half ago. As I celebrated Martinez’s victory in a bar on the Atlantic City boardwalk, the dark cloud hovering over the evening was a creeping concern about what that beautifully violent overhand left had done to Williams.

Sure enough, Williams eventually came swaggering down the boardwalk in a long mink coat as if he had won. The pallor was lifted somewhat; after all, “He looked good.†It became my lasting image of Williams, and especially given recent events, I don’t see that changing.

It’s not so much that I wanted to perpetuate some notion that Williams was okay. IT was rather that I needed to.

*****

Given my affinity for Arturo Gatti, I came to love Micky Ward by extension. Standing in Boardwalk Hall for their third fight, I remember thinking the songs for their ring walks perfectly fit both men. Thunderstruck appropriately announced the presence of the mercurial, careening Gatti, while for Ward, Whitesnake’s Here I Go Again was flawlessly poignant for a boxing lifer at the end of the line, coming out for one more grueling battle that pretty much everyone – except Ward – knew he wouldn’t win.

At that moment, I was surprised to find that despite having religiously followed Gatti’s career, I cared just as much, if not more, for Ward. He put his all into everything he did for no other reason than it was simply the way he was wired, right down to the last bell.

Almost exactly nine years later, the line for Ward’s book signing was sparse – nothing like the mob scene that showed up when my fiancée and I attended a signing with Real Housewife of Wherever Bethenny Frankel a few weeks back. For the handful of people who did show up, there seemed a certain kinship. I felt not so much a fan as a well-wisher. We didn’t come to worship at Ward’s feet, rather to simply see how he’s doing.

Ward was soft-spoken and affable. I told him how the second and third fights against Gatti were two of the greatest sporting events I’d attended, and he said, “Not me.†Laughing, he added, “Maybe the first one.†(That, of course, was the only one of the three he had won.) He signed our book, and then I insisted the three of us take a picture with the obligatory fist you always make when you pose with a boxer. My fiancée, bless her heart, gamely held up the most awkward fist I’d ever seen. Obviously, the photo is perfect.

Ward was soft-spoken and affable. I told him how the second and third fights against Gatti were two of the greatest sporting events I’d attended, and he said, “Not me.†Laughing, he added, “Maybe the first one.†(That, of course, was the only one of the three he had won.) He signed our book, and then I insisted the three of us take a picture with the obligatory fist you always make when you pose with a boxer. My fiancée, bless her heart, gamely held up the most awkward fist I’d ever seen. Obviously, the photo is perfect.

Lord knows what Ward goes through on a daily basis as a result of his former profession. He wrote in the book that he frequently forgets things and gets double vision, to say nothing of the psychological repercussions of being molested by a family friend when he was younger, a brave and cathartic revelation.

But as we left the store, I looked over my shoulder at Ward, and put simply, he looked good. He had sounded good. He had the movie to tell his story, and now he had the book.

It doesn’t take away the conflicting emotions about Gatti, et al. But seeing Micky Ward ostensibly living the good life was something of a salve. Gatti never made it out, but for all intents and purposes, his dancing partner and friend seemed to have come out okay. After standing and cheering when Gatti busted Ward’s eardrum with a hook, that’s really all I could have hoped for.