I think the best way to ponder our own inevitable passage into physical decline is to watch it happen to those who would seem invincible to such mortal constraints – and observe how they handle it.

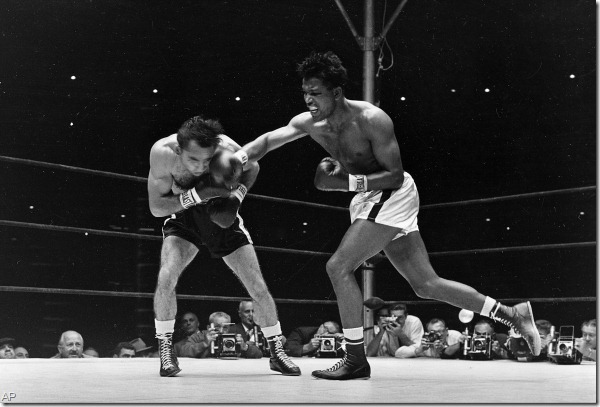

I stayed up late the other night watching a documentary on HBO on Sugar Ray Robinson, and though I thrilled at the dizzying heights he reached during arguably the greatest career a prizefighter has ever known, I was more deeply affected by what came later.

Forced to remain in the ring far too long due to financial difficulties, a man good enough to lose just one of his first 131 fights, and graceful enough to at one point pursue a career as a dancer, was punished during his final years in boxing.

Robinson’s sobering descent into Alzheimer’s, diabetes and dementia toward the end of his life was succinctly described by the late and great Ralph Wiley in the documentary: “This is the greatest fistfighter of all time. If this is what happens to him… this is what happens to them all.â€Â

Anyone who watched Muhammad Ali go through many of those same ordeals after being punished by Larry Holmes and Trevor Berbick for his inability to recognize that his time had passed, understands boxers are confronted by lasting physical and mental obstacles unlike those faced by other professional athletes, much less the rest of us.

But the sentiment is pretty much universally the same: None of us are designed to be young forever, and those best able to adjust their mentality and expectations are the ones most at peace with themselves as their careers – and lives – wind down.

To borrow a cue from Grantland, my favorite sports book is When Nothing Else Matters, Michael Leahy’s account of the final act of Michael Jordan’s playing career, his depressing stint with the Wizards. Leahy is unflinching in his depiction of the willingness of Jordan’s mind juxtaposed against the inability of his body to follow suit.

To borrow a cue from Grantland, my favorite sports book is When Nothing Else Matters, Michael Leahy’s account of the final act of Michael Jordan’s playing career, his depressing stint with the Wizards. Leahy is unflinching in his depiction of the willingness of Jordan’s mind juxtaposed against the inability of his body to follow suit.

It’s not that I had previously desired to see Jordan in particular broken down; I’ve long been a fan. But in certain ways, watching a humbled Jordan drag his tendinitis-ridden knees around the court was emboldening. Perhaps it helps the mortals among us cope with the gradual tearing down of our youthful invincibility to know that nobody is immune – not even the most gifted.

Even after a three-year layoff and a debilitating finger injury sapped him of his ability to compete at the highest level, Jordan never would admit to himself that he was no longer athletically equipped at 38 to deal with young lions like Vince Carter and Paul Pierce. Jordan would have nights where his body would comply with what he demanded of it, and he’d put up a familiar 40 points. Then the next night, in large part as a result of his hubris, Jordan’s knee and wrist would stiffen and he’d put up a 7-for-21, five-turnover clunker.

If Jordan had adjusted his modus operandi during that first Wizards year, taken on fewer of the minutes and burden as his doctors implored, his final comeback might have been a positive memory instead of a chapter even his staunchest fans basically refuse to acknowledge. But that would have required him to be something less than The Man, and that was the only world he knew.

The current NBA lockout has us wondering – rightfully – about what our longtime NBA icons will look like on the other side after losing precious moments of the time allotted to play at a high level. But besides pondering when their skills and athleticism begin eroding, I’m interested to see how they’ll react when that happens.

Will someone like Kobe Bryant – about to turn 33, but with many miles on his sinewy frame – simply press on as a steadily diluting version of what we’re accustomed to? Will he instead subjugate his game and his alpha dog status in the interest of doing whatever is needed to win a championship? Or will he simply disappear when he starts to slip? (I can’t imagine that last one either.)

*****

Admittedly, and perhaps unsurprisingly, this comes from a personal place. Not that I was ever Carl Lewis or anything, but I turned 32 a few days ago and am simply not the athlete I was in my late 20s.

Three years of persistent leg injuries have rendered me a somewhat lesser runner, leaving me wistful about the two marathons I ran just a few years ago. An hour of hard basketball leaves me sorely in need of ice and wondering if the painless and tireless four-hour marathon hoop sessions of my early 20’s actually existed.

Even as the injuries started to pile up – my hip, then a strained calf, then chronic shin pain – I insisted to myself that if I saw enough doctors, got enough acupuncture and stim treatments and took enough time off, it would all heal and I would still be what I always was.

But as months passed and my body wouldn’t hold up under my previous regimen, I started coming to grips. I downgraded to shorter runs, and started to liberally ice after I ran. I learned the value of rest, recovery and – begrudgingly – embraced the occasional skipped workout. I’m not what I was, but I’m content with where I’m at.

As Eminem’s character said in 8 Mile, sometimes you need to stop living up there… and start living down here. And it does soothe to know that nobody is immune to the limitations of aging. The soaring Gods I’ve always looked up to – the Jordans, the Alis, the Ken Griffey Jrs. – all have to eventually come down to earth. This doesn’t belittle their previous achievements; quite the contrary, Bulls-era Jordan and first iteration of Griffey on the Mariners seem that much more impressive based on what they were no longer able to do later.

The way our modern-day sports heroes are canonized, it’s difficult to imagine someone like Kobe Bryant, a mostly unparalleled star in a sport that highlights individuality, accepting a lesser role than what he’s accustomed to under any circumstances. That said, Kobe has always seemed to possess a certain savvy that might lend itself to a gentle decline rather than a crash and burn.

Down the road, more of the greatest players of this generation will face similar crossroads, most notably and interestingly LeBron James, who was born and raised to be a singular star. But he’s no longer a spring chicken, not after eight NBA seasons (!) averaging over 40 minutes per game.

As LeBron becomes unable to rely on his physicality, will he evoke the 2003 David Robinson, gracefully modifying his game to fit in on a championship team? Or will he be the 2001-03 Jordan, obstinate and infuriated by his body’s failings? His work with Hakeem Olajuwon speaks to his desire to change his game, as his chemistry issues while integrating into a star-laden Heat squad perhaps don’t profile as positively.

All that remains to be seen. But we do know at least one thing we have in common with the demigods: Try as you might, you can’t hold on to your youth once it starts to slip through your fingers. It’s all about figuring out how to best mentally and physically adjust.

As Kobe and LeBron age, they can learn if they choose from their predecessors. We’re generally able to take our accomplishments and memories with us, but when it comes down to brass tacks, to borrow from Incubus, it’s not who you were. It’s who you are.